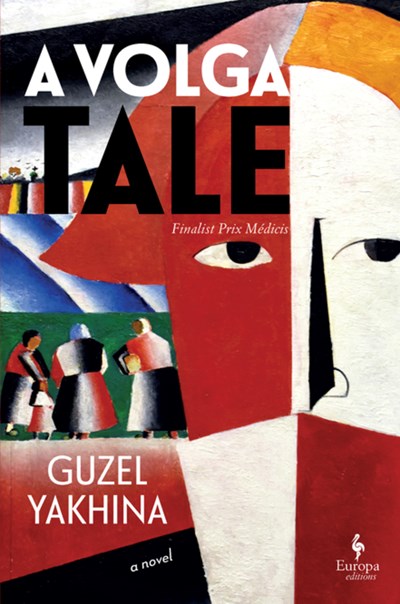

A Volga Tale by Guzel Yakhina

A delightfully translated novel combining fairy tale and historical fiction in a fully satisfying story of a misfit struggling to sustain life in a perilous time.

One of the most appealing and remarkable things about good books is their ability to evoke the flavor of a place, a people or a time. In the case of A Volga Tale, Russia is rendered palpably present: the sounds, the smells, the weather, the food, the daily life of its people, not to mention the dynamic politics and cultural upheavals of the post-revolutionary years. The reader is transported by this deftly limned tale of the Volga German Soviet Republic, a region settled by Teutonic immigrants welcomed by Catherine the Great and who would remain until the second world war.

Melding myth and fact, urban and rural, politics and philosophy into a fascinating story of a misfit in a time when misfits were hunted and eliminated provides a matrix for this masterfully written novel. The protagonist, Bach,a citizen of the small town of Gnadenthal (a toponym meaning “Valley of Mercy” in German) is a hapless school master given to nocturnal expeditions during violent storms. He seems to derive energy and meaning from the extremes of weather on the verges of the steppe where the great Volga separates mountains and plains. In everyday life he is hesitant, meek and seems rudderless until he is summoned to the homestead of a powerful landowner on the far side of the river. Tasked with educating the land baron’s sequestered daughter he inevitably falls in love with her and she with him, to the peril of both. As things turn out they find themselves living together in isolation with Bach making nightly trips across the water into the village to procure milk for their love child. Other than the dependence on Bach’s unlikely association with a party official who loves the fairy tales Bach provides him they are self-sufficient and insulated from the social and political upheaval occurring in the post-revolutionary times. Reality catches up to them, however, in a variety of unpleasant ways.

The translation of this work is exquisite: it is as though it were written in English, a feat that is not always achieved when our language is used to elucidate something written in another, especially one as different from ours as Russian. The narrative not only flows cleanly it is lyrical and lovely and entirely delightful. There are also extensive notes at the back of the book to explain some of the more arcane terms and ideas that may be unfamiliar to modern American readers. One will most likely find that they are not needed to absorb the meaning but it is good to have them for deeper understanding. I would recommend this to anyone who loves historical fiction especially if the reader is interested in other cultures.