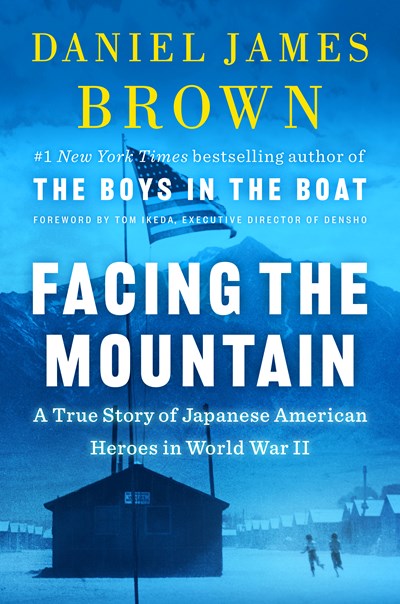

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown

The story of the Japanese American soldiers who fought for the U.S. against the Nazis in spite of their treatment by our government. Heroism and patriotism were displayed both on the battlefield and in internment camps by these worthy citizens.

Note: This was written two days after six Asian American women were killed in Atlanta, GA in a year when over 3800 racially motivated attacks upon people of Asian heritage were perpetrated in the U.S.

After Dec. 7, 1941 the mood in the U.S. towards those of Japanese descent became ugly and bitter. Without regard to whether these folks were citizens, born in this country, or documented immigrants with longstanding community status as taxpayers and upright, contributing members of our society they were reviled, publicly attacked, designated enemy aliens and interned in what can only be called concentration camps by the hundreds of thousands. Driven out of their homes, deprived of their belongings and property and herded into ill-heated, overcrowded and substandard housing where they were guarded day and night by machine-gun-carrying guards, they were given exactly the treatment the Nazis accorded their designated “undesirables”. Any photo of a “Relocation Facility” will show little or no difference to any camp in Germany, Poland or other European locations run by the SS. Except this was “the land of the free, home of the brave”. Freedom and bravery were thin on the ground, it seems.

But not in the hearts and minds of those who were being so abused. By the thousands, young Nisei (second generation) Japanese volunteered to join the U.S. military and fight for the protection of the country they considered home. While their fathers were being kept in military prison enclosures and their sisters, mothers, aunts and uncles and sometimes their children were restrained and segregated from outside society, they were undergoing grueling training in boot camps, learning deadly skills that would make them useful to the Army.

These are the personal stories of these patriots, Americans in every sense, putting their bodies and lives in peril despite being called “Japs”, “nips” and any number of other demeaning epithets in the streets, shops, city halls and even newspapers. It mattered to them only that they show honorable loyalty to the nation that was theirs, as much as any cornfed midwestern farm boy, Texas ranch hand or Brooklyn-born youngster.

Told in alternating sequences, the accounts of the fighting 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the repressed lives of those left behind in the camps, these heart-rending narratives thrust into the light the real lives of a shamefully and unjustly treated people. Varying from harrowing reports of the deadly combat in extreme conditions to the often uplifting and inspirational methods of a people imprisoned to make a life of some comfort and meaning, these are heroic stories of good and righteous common citizens.

With a straightforward and unadorned style, avoiding hyperbole or rhetoric, the author shows how individual members of the Nisei community and their parents, the Issei (immigrants born in Japan, but living in the U.S.) contributed to the ultimate victory over the Nazis, securing a peace which they would not be allowed to fully enjoy, even after returning as one of the most decorated outfits who fought in WWII. The racial epithets and discrimination did not end with the war. It is a disgraceful chapter of our history, but one which should not be forgotten, especially in today’s climate of fear and prejudice against all immigrants.

I found this book to be difficult to read and at the same time impossible to put down. The residual shame that accompanies the reader’s cultural guilt competes with a deep admiration for these noble Americans.